We’ve all seen them (and many of us have cried a little) — those YouTube videos of little children reuniting with a returning soldier, often their mom or dad. The child leaps into their parent’s arms and clings on for dear life, tears streaming down their little face. It’s a moment of pure joy. But what happens in the hours, days, and months after those happy reunions? And, even more concerning, what goes through a child’s mind when mom or dad are first deployed? There aren’t too many uplifting online videos depicting those departing moments…because, all too often, they are very traumatic.

The United States military is an enormous operation. There are approximately 1.3 million active duty personnel serving in the U.S. military with an additional 800,000 reserve forces (as of September 2017), according to Defense Department personnel data. This means that 0.4 percent of the American population is an active military service-person. While most work at home, the U.S. has nearly 800 military bases around the world and, although deployment numbers fluctuate daily based on the needs of commanders and shifting missions, a rough estimate is that 200,000 troops are currently deployed overseas. U.S. Central Command says that between 60,000 and 70,000 U.S. troops are now in the Middle East and the Pentagon has directed about 4,500 additional troops to the region after the recent drone attack which killed Major General Qassim Suleimani, an Iranian security and intelligence commander.

Working in the military is a uniquely challenging job, a calling for many, a family tradition for others. Most members of the military come from middle-class neighborhoods, just like the original participants in the ACE (Adverse Childhood Experiences) study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Kaiser Permanente in the mid-1990s. Increasingly, women are serving in high-powered or even combat roles. As a society, we acknowledge the danger and dedication this takes, which is why we often thank these brave men and women for their service when we encounter them. But are there more insidious dangers lurking at home? Military families, like all families, need to guard against ACEs. While deployment is not an ACE in itself, the circumstances it results in can be detrimental to healthy childhood development and need to be guarded against.

Sudden Loss

One aspect of the military that distinguishes it from other jobs, even dangerous ones, is the very short notice afforded military personnel when they are suddenly deployed. Typically, troops get their orders to deploy many months in advance. In times of stability, soldiers can expect to spend anywhere from three, to six, to twelve months away. Everyone in the unit has ample time to get their ducks in a row before heading overseas. But, when urgent needs arise or sudden volatility occurs, they must be ready to leave in as little as 18 hours. That’s less than a day to cancel plans, call loved ones, rearrange commitments, and comfort young children who suddenly have to be told that mommy or daddy is going away. Birthdays, sports games, recitals, and graduations may be missed. These dates mean a great deal to children and can’t be rescheduled. These precious moments can’t be replaced and can result in feelings of apprehension, abandonment, and resentment.

Deployment does results in one key ACE, however — the loss of a parent. While the original ACE study asked about parental loss due to death or incarceration, it also asked about divorce. It’s clear that any sudden long-term separation from a parent can throw a child’s world into chaos. It may not help much to explain that, in the vast majority of deployment cases, the absent parent returns, safe and sound. Children perceive time differently. Tomorrow seems like forever away, so a deployment of a few months is almost a lifetime. Children are also very literal up to the age of about 11. If you promise to take them out for ice cream and then have to change those plans, you are “a liar”. Disappointing a young child, who likely finds it difficult to delay gratification, because of a deployment can seem like a crushing blow to them.

In fact, each stage of deployment can be fraught with anxiety and stress of different kinds.

Pre-Deployment

A deploying service-person in the family throws established routines into chaos. Children experience unexpected disruption and uncertainty. Even experienced military families find the adjustment jarring. The shock of a sudden departure of a parent can leave children feeling a kind of bereavement over the loss, which may manifest itself in sullenness, anger, violent outbursts, or refusing to talk or cooperate.

Deployment

The absence of one parent can put undue burden on the remaining parent, even in the most well-adjusted families. Deployment can bring financial and emotional deficits, placing children in the home at greater risk for adversity. In some cases, children need to move from their established home to live with grandparents or other caregivers, a dramatic disruption at a time when they crave the sense of security structure brings. While away, the military parent is at constant risk. Whether or not a child has been told that their parent may be wounded or even die, they are very intuitive and pick up on the anxiety and fear in the home. Even very young children know their routine has changed and may start to “act out”.

Post-Deployment

While disruption results when service-people deploy, it happens again when they return. This means a double dose of unsettling emotions for young brains that are still developing and vulnerable to the negative effects of toxic stress — the kind of stress caused by repeated activation of the fight, flight, or freeze reflex, which results in atypical levels of adrenaline being dumped into the body.

PTSD and Other Issues

When service personnel return home, they can bring serious challenges with them. PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) varies by war/operation but affects between 11% and 30% of service-people. Symptoms can include flashbacks, nightmares, and severe anxiety, all of which can be terrifying for a child to witness. PTSD sufferers can experience problems relating to others, too. They can have trouble showing feelings or affection, difficulty sleeping, irritability, angry outbursts, lack of concentration, and a heightened startle response (”jumpiness”). In the most extreme cases, the returning parent is barely recognizable as the same person who left, which is undoubtedly traumatic for a child.

Shannon Hawkins, Director of Community Engagement at a private health foundation that funds Center for Child Counseling’s Fighting ACEs campaign, recalls her childhood as a military kid. “Noise, or any type of unexpected sound, affected my father deeply after he returned from serving. He would jump at the slightest thing and, as a child, I remember how quiet we had to be inside the house to avoid triggering him. It was a new reality after he came back.”

Countless families report the same experiences and the children in these homes may have difficulty with:

• Fears and worries about the parent-soldier’s safety, especially if exposed to combat

• Absence/separation from the parent-Soldier, especially during lengthy deployments

• Changes in family routines, roles, and responsibilities

• Intense emotions in the family

• Changes in the relationship with the deployed and nondeployed parents

• Relocation to a different geographical area to live with a new caregiver

• Exposure to troubling media coverage, especially if the mission is in a combat zone

• Reintegration of the parent-soldier into the family

Heightened Risk Factors

It’s important to remember that one of the ACE study questions addresses mental illness (“Did you live with a household member who was depressed, mentally ill, or attempted suicide?”). With rates of depression higher among military personnel than the civilian population, this ACE is a definite risk factor for military children.

Domestic violence was another ACE identified in the original study (“Did you see or hear household members hurt or threaten to hurt each other?”). There was a 177% increase in Intimate Partner Violence within the military between 2000- 2010 at al time when national rates were decreasing. Clearly, this is another potential ACE risk factor for military children.

A third potential ACE involves substance abuse (“Did you live with someone who had a problem with drinking or using drugs?”). Studies indicate a higher prevalence of binge drinking among military personnel than the population at large.

Benefits for Military Families

As a counterpoint to some of the challenges facing military families, the military does provide benefits for its children not afforded to the everyone in the civilian population. These can be considered protective factors.

• Universal healthcare coverage

• Comprehensive/affordable daycare

• Steady employment (lack of extreme poverty/lower rates of physical neglect)

• Paid family leave for both parents

• In general, military families score higher on scales for parental education, residential stability, and positive family function

Despite the uncertainty and possible exposure to ACEs that threaten military families, the majority of them find ways to cope and manage very well. Studies reveal that most people who enlist in the military do so for positive motives including patriotism, altruism, and self-improvement. The military instills routine, discipline, and the idea of self-sacrifice. When taught appropriately, these lessons can help a child learn resilience. Remember that resilience is the ability to be flexible and thrive during times of undue stress, or the ability to rebound from adversity as a strong, healthy, more resourceful person. Children’s reactions to the stress of deployment, their coping skills, and the level of their resilience can differ depending on their age, stage of development, personality, prior life experiences, and former challenges, as well as the number and efficacy of the support systems available to them. We can all play a part in helping children thrive during their parent-soldier’s deployment.

What Can You Do?

Young children may experience feelings of abandonment or anger when a parent leaves, regardless of the reason. Some children don’t know where to turn with the big feelings they are experiencing. Others may be told to be proud or “be brave for Mommy,” which may contradict the complex sadness or anger they are naturally feeling.

Secure relationships, effective communication, critical thinking, and thorough preparation are key to successful family functioning during deployment.

Keep the Lines of Communication Open: Adults can gain insight into what children understand about their parent’s deployment by listening to what they have to say and asking them about their thoughts and feelings. Rather than avoiding talk of the absent parent, it helps children to speak freely, express their concerns, and work through their emotions. Sometimes, acknowledging a feeling or a fear can go a long way to dispelling it.

Try to Retain a Routine: As far as possible, provide security for children in military families by giving them the comfort of established routines. Children crave boundaries, which make them feel safe. Keeping to a set schedule where children know what to expect helps to minimize anxiety about the unknown, which they are naturally feeling.

Provide Regular Reassurance: When the topic of the military or war comes up in the media or at school, you should share with your child anything you know about the safety of their parent. You might say: “I know you saw on the news today that they were fighting in Tehran. Mommy isn’t anywhere near there. She is safely working in the communications office very far away from all that.”

Craft a Countdown: It may help to create a tangible way of showing that time is passing. A simple chalkboard updated daily showing the days until dad returns, for example. Or, you can find two jars and a number of marbles or pennies correlated to the number of days your loved one will be away. Put all the marbles or pennies into one jar. Each day, move a marble from the “days left” jar to the “days passed” jar, so your child can see the time diminishing and that things are moving towards reunification.

Stay Connected to the Deployed Parent: A regular connection, if possible, provides vital reassurance to a young child. These days, technology can facilitate face-to-face video calls; letters, emails, and photos also help children to stay connected.

Make a Deployment Bucket List: You can help your child craft a list of things they look forward to doing when mom or dad returns. It’s great for them to set some goals for themselves to work towards, too. For example: “By the time dad gets back, I will be able to ride my bike.”

Establish New Family Traditions: Even little tokens help maintain a sense of family in the absence of one parent. You can share memories of “funny things dad does” at the dinner table. You can make your own rituals and routines to build cohesion – the key is that you do it together and on a regular schedule.

Art Projects & Journaling: Some children draw or paint pictures and build a portfolio to share when mom or dad returns. Older children can write diary entries to share their private thoughts, although it’s important to encourage them to share openly with a trusted adult rather than keeping feelings bottled up inside. Pinterest has some great military art project ideas and ideas for Veterans Day that are suitable for kids of differing ages.

Visit a USO Center: The military offers many support sites (online and tangible) where military spouses and children can find support.

In some cases, the benefit of being raised in a military family far outweighs the potential ACEs it might bring. Michelle Brown, whose father served in the United States Air Force until she was 16, says: “The lessons I learned as a ‘military brat’ made me who I am today. There may have been some hardships, like having to make new friends after every move, but my parents also taught me coping skills. Now, I make friends easily, I am dedicated, and I’m tough. The military equipped me for life’s changes. I don’t regret a thing about growing up military.”

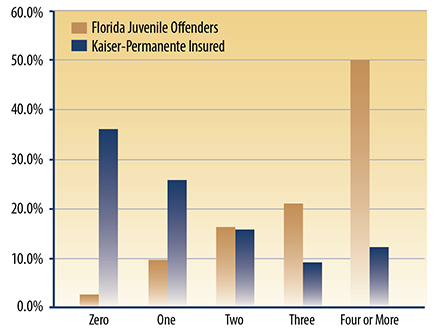

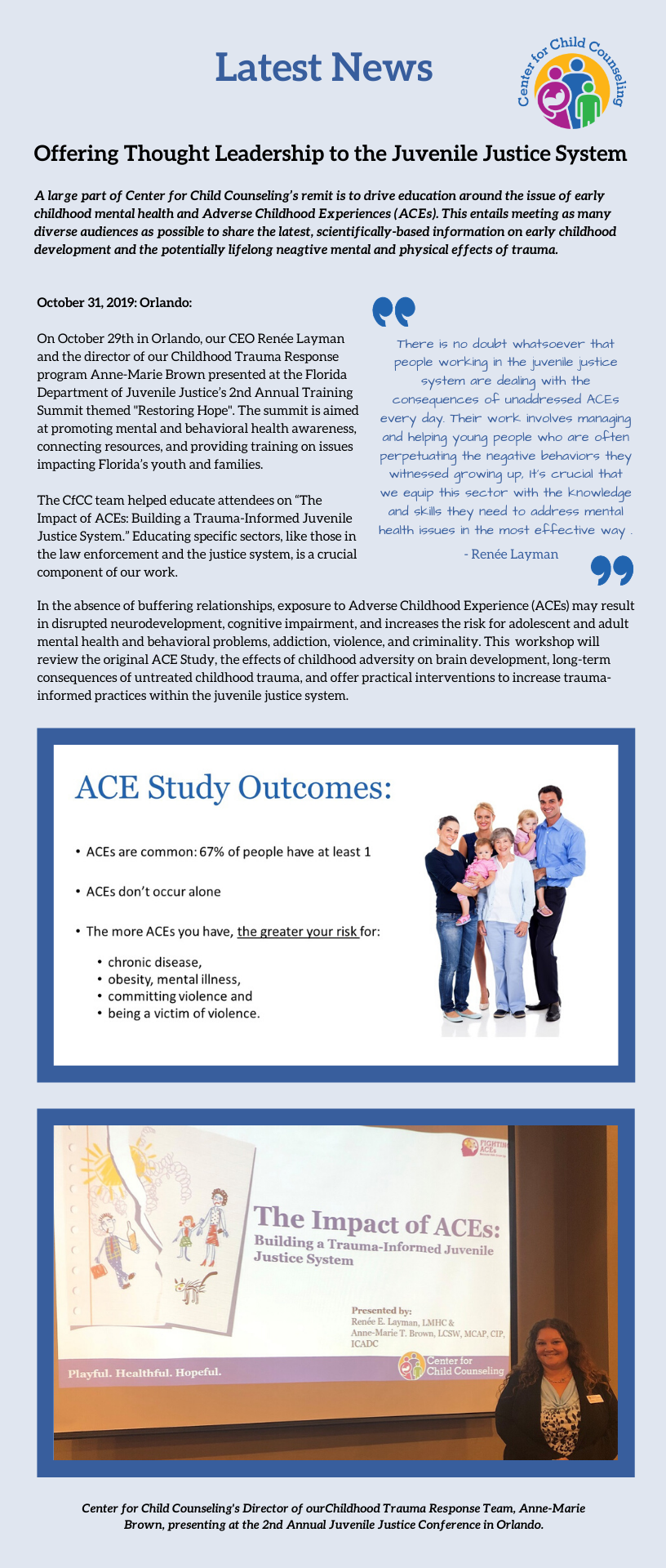

In the United States, there is undoubtedly a link between literacy and incarceration. 85 percent of all juveniles who interface with the juvenile court system are functionally low literate. These are likely youngsters who have been struggling at school. Partner with that the fact that juvenile incarceration reduces the probability of high school completion and increases the probability of incarceration later in life and you can see that early negative indicators like poor social skills and self-regulatory difficulties (often identified as early as kindergarten) are reliable in tracking poor future outcomes. It seems depressing to be betting against our children in this way but the correlation between early struggles and ultimate incarceration are so clear that these metrics are, sadly, reliable. It’s our job to intervene and disrupt the pipeline of despair that moves children from childhood adversity to contact with the juvenile justice system to adult incarceration. We need to help children before they fall apart through prevention and intervention services and improved education for those working in the juvenile justice system.

In the United States, there is undoubtedly a link between literacy and incarceration. 85 percent of all juveniles who interface with the juvenile court system are functionally low literate. These are likely youngsters who have been struggling at school. Partner with that the fact that juvenile incarceration reduces the probability of high school completion and increases the probability of incarceration later in life and you can see that early negative indicators like poor social skills and self-regulatory difficulties (often identified as early as kindergarten) are reliable in tracking poor future outcomes. It seems depressing to be betting against our children in this way but the correlation between early struggles and ultimate incarceration are so clear that these metrics are, sadly, reliable. It’s our job to intervene and disrupt the pipeline of despair that moves children from childhood adversity to contact with the juvenile justice system to adult incarceration. We need to help children before they fall apart through prevention and intervention services and improved education for those working in the juvenile justice system.