For the past few years, our blog has shared information on ACEs: citing world-renowned studies and organizations, sharing solutions and strategies, and communicating ideas for building a more trauma-informed community. We know that knowledge is empowering, so a big part of our work involves letting people know about the lifelong mental and physical impact Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) have on children. At some point, however, it helps to turn our attention away from theories and refocus it on reality…the real children who are affected, the real work we do, and the very real need for financial support.

But first, let’s recap the basics…

The Undisputed Facts

- ACEs are traumatic experiences that occur in childhood as a result of abuse, neglect, or household dysfunction.

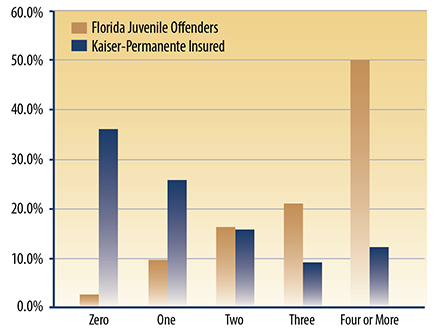

- ACEs were first explored in a study conducted in the mid-1990s by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and insurance giant Kaiser Permanante.

- More than half the US population has at least one ACE (out of a possible score of ten); many people score far higher.

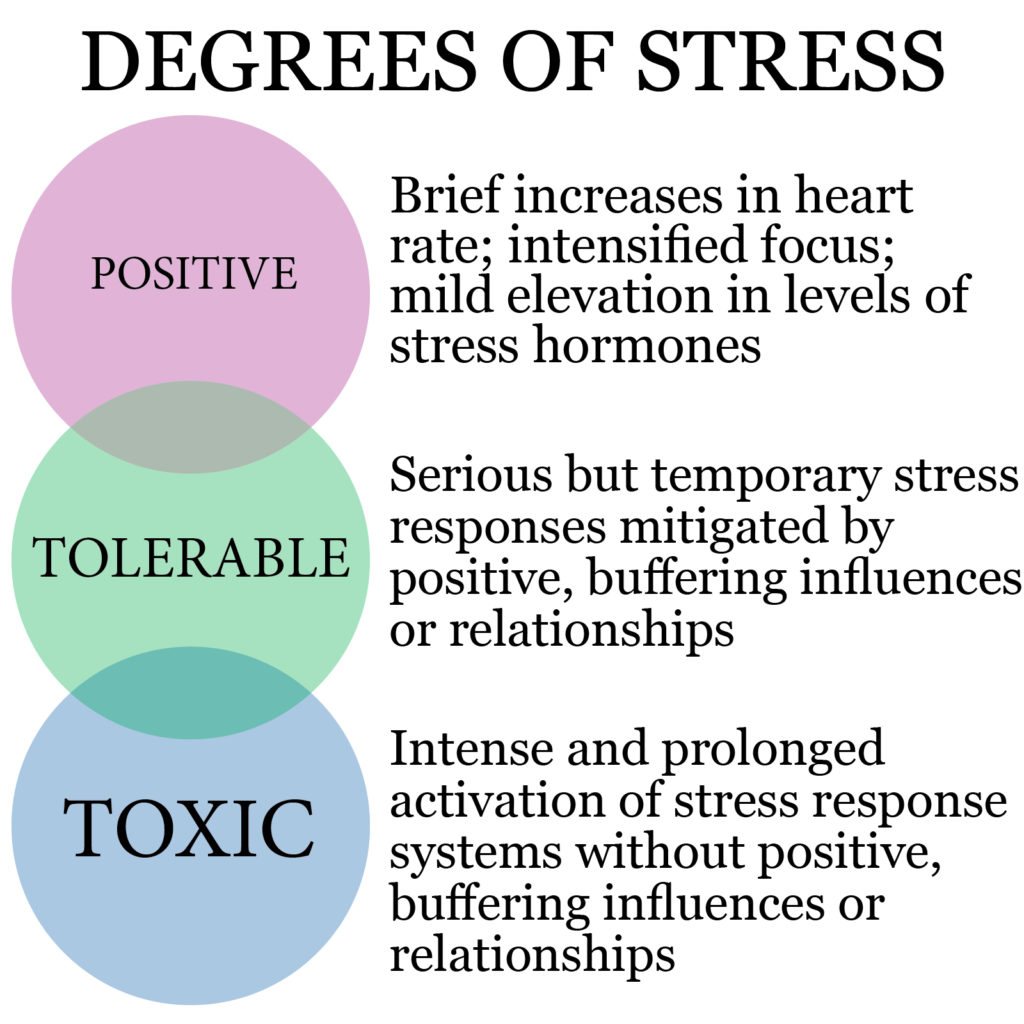

- Breakthrough research in neurobiology shows that ACEs disrupt neurodevelopment and can have lasting effects on brain structure and function, which is why ACEs can dramatically alter the course of a person’s life.

- ACEs are a root cause of many social, emotional, and cognitive impairments that lead to health risks, increased exposure to violence or revictimization, disease, disability, and premature mortality.

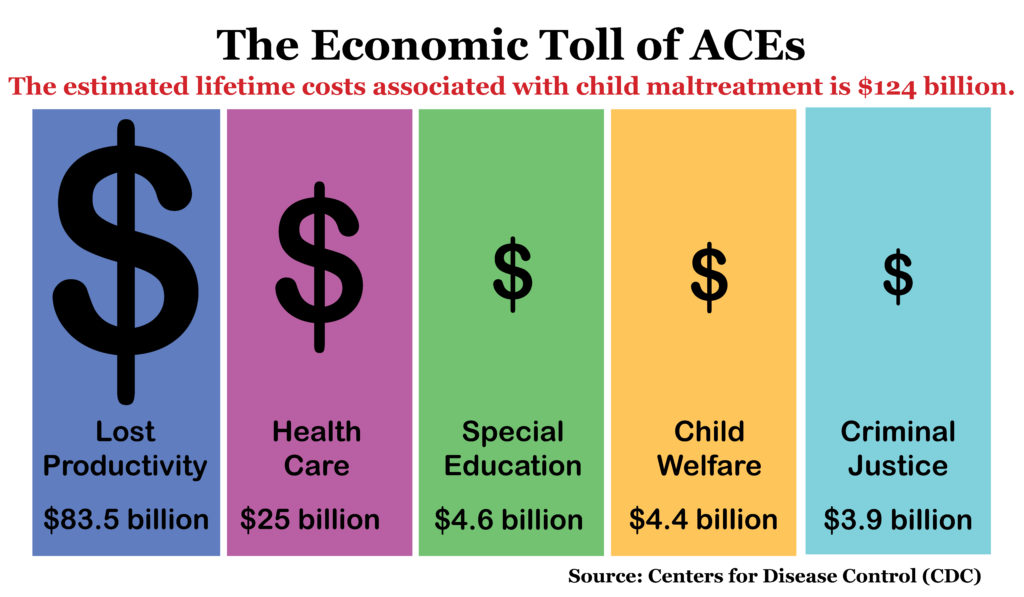

- ACEs have huge financial costs to society, too. They burden social and healthcare systems and result in lost productivity.

- The good news is that introducing just one positive, adult influence to buffer the effects of ACEs can make all the difference to a child.

- Children can also be helped to develop their innate resilience, helping them cope with and overcome adversity and ultimately lead full, happy lives.

At Center for Child Counseling, we address all these issues by focusing on very young children because this approach offers children the best possible chance to heal.

When some people look at this issue, they are compelled by their hearts to act. For others, a concrete, facts-based argument is more persuasive. Setting aside the desire we all have to protect abused of children, as taxpayers we should be concerned about the cost of unaddressed childhood adversity, too.

The Real Cost to Communities

The CDC estimates the total lifetime economic burden resulting from new cases of fatal and nonfatal child maltreatment in the United States was approximately $124 billion in 2008. A decade later, that cost has undoubtedly skyrocketed. In sensitivity analysis, the total burden is estimated to be as large as $585 billion.

Another study conducted in Washington State showed that up to 67% (an astonishing two-thirds) of behavioral and physical health problems that cause people to seek social services are attributable to ACEs. Many of these services are funded by the taxpayer. There is no doubt that doing the right thing morally (addressing the suffering of children) will, in the long-term, save us a great deal of money.

Just One Example Costs Us Billions

Let’s consider just one damaging adult behavior – excessive alcohol use. An ACE score of just 1, (which covers six out of ten Americans) can cause sufficient trauma to make a person twice as likely to become an alcoholic. Alcoholism is the most common addiction in the United States with 17.6 million people–one in every 12 adults–suffering from alcohol abuse. Several million more engage in risky, binge-drinking patterns that could lead to problems with alcohol. The cost of excessive alcohol use in the United States reached $249 billion in 2010, or about $2.05 for every alcoholic beverage consumed!

But beyond all this data are real children and we need to think about them as individuals. Brutal Russian dictator, Joseph Stalin, understood how easily big issues can become banal. He famously said: “If only one man dies of hunger, that is a tragedy. If millions die, that’s only statistics.” Taking in the big picture can sometimes obscure the very human toll of an epidemic or even dilute the urgency to act. We look at every one of our clients as a precious individual. Our work is focused on quality care for one child and one family at a time. Let’s consider some of the children we help every day.

The Real Children

The greatest heartache of watching children struggle is the knowledge that each child is brimming with potential. When that potential is fulfilled, the world benefits in uncountable ways. The converse is true, too. The world loses when children don’t grow up to thrive and contribute.

At Center for Child Counseling, we’ve helped children like siblings Jessica and Josiah, who experienced severe violence in their home and eventually witnessed their parents’ murder-suicide. Four-year-old Shawn was removed from his substance-addicted mother because he was living in dangerous conditions after a neighborhood drive-by shooting riddled his home with bullets. Four-year-old Raj, three-year-old Nicola, and two-year-old Titus were removed from their home after their parents’ overdosed on opioids. These three tots were so neglected that their little bodies were shutting down from severe malnutrition.

Of course, we help many other children, too. Children who are struggling to adjust to school or children who aren’t coping well with a separation or divorce in the family. We can help them all.

The greatest return on any investment comes when that investment effects future generations. Breaking the intergenerational cycle of abuse, neglect, and dysfunction that defines an ACEs household offers exponential benefits going forward. It results in stronger communities, a lower burden on social services, an larger tax base, and greater security for schools and neighborhoods.

“For us, fighting ACEs is a moral imperative as well as good financial sense,” says Center for Child Counseling’s CEO, Renée Layman. “A society that turns a blind eye to the suffering of children isn’t one we would want to live in…and if we do choose to live in it without addressing the issue, then we choose to rain down a storm of societal ills on ourselves and future generations.”

We Know Better, We Must Do Better

Rather than throwing up our hands and bemoaning the sky-high costs and devastating prevalence of ACEs, at Center for Child Counseling, we’ve chosen to take action.

We currently run seven robust programs through which we offer direct services to children and families and educate the community to recognize and address the issue of ACEs. While some programs receive full or partial funding through public agencies, grants, or government programs, there is a lot of work that remains sadly unfunded. In other words, we could be doing so much more!

Funding is needed to implement the full model of our existing projects like our School-Based Mental Health Program, which has crucial prevention and early intervention components. We need support to grow skilled, experienced therapists, ensuring that Palm Beach County offers cutting edge programs and advocacy that is based on best practice and evidence-based models. You can help us by taking a training on ACEs and many other subjects through our Institute for Clinical Training or by simply enjoying yourself at one of our upcoming events.

If you see the logic of helping very young children before they fall apart, or if the black-and-white economic argument is more powerful to you, please consider a donation or corporate sponsorship, As the year draws to a close, you have the opportunity to make a real difference in a real child’s life. Because beyond the data and the statistics, a little child is waiting, asking for help from a caring therapist who can undoubtedly make their 2020 a much happier, healthier year.

Sign up now for news, events, and education about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and promoting resilience.

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive emails from: Center for Child Counseling, 8895 N. Military Trail, Palm Beach Gardens, FL, 33410. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email.

In the United States, there is undoubtedly a link between literacy and incarceration. 85 percent of all juveniles who interface with the juvenile court system are functionally low literate. These are likely youngsters who have been struggling at school. Partner with that the fact that juvenile incarceration reduces the probability of high school completion and increases the probability of incarceration later in life and you can see that early negative indicators like poor social skills and self-regulatory difficulties (often identified as early as kindergarten) are reliable in tracking poor future outcomes. It seems depressing to be betting against our children in this way but the correlation between early struggles and ultimate incarceration are so clear that these metrics are, sadly, reliable. It’s our job to intervene and disrupt the pipeline of despair that moves children from childhood adversity to contact with the juvenile justice system to adult incarceration. We need to help children before they fall apart through prevention and intervention services and improved education for those working in the juvenile justice system.

In the United States, there is undoubtedly a link between literacy and incarceration. 85 percent of all juveniles who interface with the juvenile court system are functionally low literate. These are likely youngsters who have been struggling at school. Partner with that the fact that juvenile incarceration reduces the probability of high school completion and increases the probability of incarceration later in life and you can see that early negative indicators like poor social skills and self-regulatory difficulties (often identified as early as kindergarten) are reliable in tracking poor future outcomes. It seems depressing to be betting against our children in this way but the correlation between early struggles and ultimate incarceration are so clear that these metrics are, sadly, reliable. It’s our job to intervene and disrupt the pipeline of despair that moves children from childhood adversity to contact with the juvenile justice system to adult incarceration. We need to help children before they fall apart through prevention and intervention services and improved education for those working in the juvenile justice system.