Think about a toddler who is just learning to walk. Picture the number of times that toddler stumbles and tumbles. Researchers at New York University, directed by Dr. Karen Adolph, showed that newly-walking infants travel about 2,360 steps each hour. They also fall down an average of 17 times during that same period. Imagine you failed at something you were trying to achieve 17 times every hour. You’d be experiencing a setback once every 3.5 minutes – very disheartening. But do toddlers stop trying to walk successfully? Never. They get up again and again and keep moving. This is a compelling way to describe resilience. As Oliver Goldsmith, an 18th century Irish poet, put it: “Success is simply standing up one more time than you fall down.”

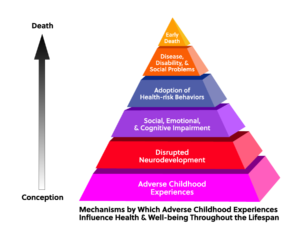

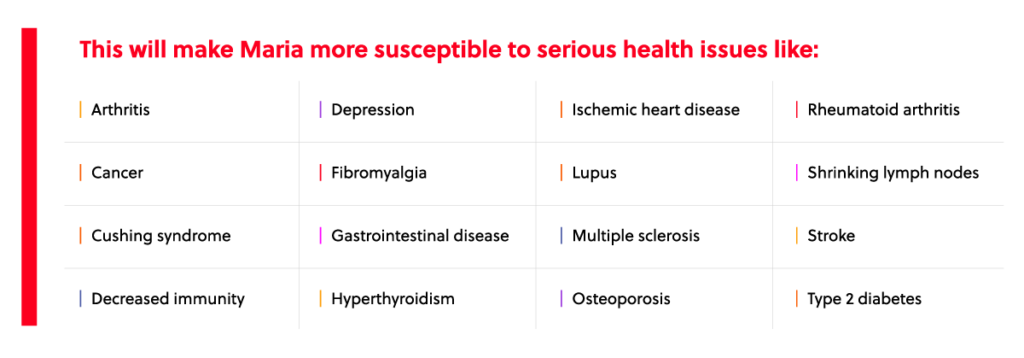

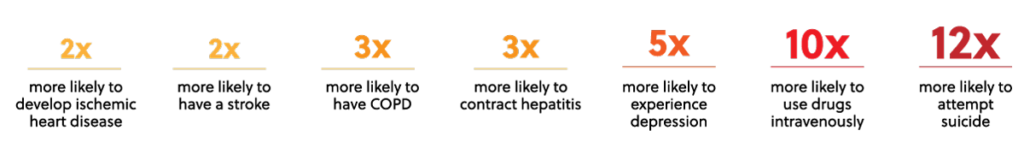

What makes some people so resilient and what does this have to do with ACEs? As we’ve learned, ACEs are Adverse Childhood Experiences that have a dramatically detrimental effect on a person’s lifelong mental and physical health. The statistics for those with high ACE scores seem bleak. They suffer from more diseases, greater levels of depression, alcoholism, and substance abuse. They die, on average, 20 years younger than those with no ACEs. But there is hope and resilience might be the key.

What is resilience?

Resilience is the ability to bounce back from life’s difficulties. It can be described as a varied and dynamic mix of many traits like determination, toughness, optimism, faith, positivity and hope. Resilience isn’t necessarily something a child is born with, although scientists now believe that certain children are genetically predisposed to higher levels of resilience. But the good news for all children is that resilience is like a muscle - the more you exercise it, the stronger it grows, especially in very young children where neural pathways are still forming and thinking patterns are elastic.

ACEs are only one half of any equation to try and predict a child’s future course. While each child is exposed to different degrees of trauma, they also have their own unique set of characteristics that can protect them against that trauma. A high ACE score is not a guarantee of negative outcomes in life. It’s a big warning sign but no child is doomed by their ACE score.

Two crucial factors are at play: 1.) The child’s own biological and developmental characteristics (their “nature”) and 2.) external influences from their family, community, and support systems. When these influences are positive, we call them “protective factors”. Protective factors help explain why some people who have sustained a great deal of adversity as children fare relatively well in adulthood.

Like a balancing scale, resilience is the result of interactions between a person’s ACEs on one side and his or her protective factors on the other.

How does resilience develop?

Researchers continue to refine their understanding of the components and processes involved in resilience. However, there is agreement about a variety of important conditions that support resilience.

• Close relationships with competent caregivers or other caring adults

• Parental resilience

• Caregiver knowledge and the use of positive parenting skills

• Having a sense of purpose (through faith, culture, identity, etc.)

• Individual competencies (problem solving skills, self–regulation, autonomy, etc.)

• Opportunities to connect socially

• Practical and available support services for parents and families

• Communities that value people and support health and personal growth

Protective factors help a child feel safe more quickly after experiencing the toxic stress of ACEs. Protective factors can neutralize the physiological changes that naturally occur during and after trauma. This protects the developing brain, the immune system, and the body as a whole from negative effects.

If the child’s protective factors are firmly in place, development can be sound, even in the face of severe adversity.

If these protective factors are inadequate, either before or after the traumatic experience, then the risk for developmental problems is much greater. This is especially true if the environmental hazards are intense and prolonged.

Resilience can be the antidote to ACEs

The negative consequences of ACEs can be counteracted with support, care, and appropriate intervention. Through positive relationships, children learn to develop crucial coping skills. They know that they are not alone, and they adopt healthy ways to process stress.

When children are taught coping mechanisms at a young age, they start to exercise their resilience muscle. As a child moves into maturity, they need to keep working their resilience muscle. When they do, they continue to grow stronger and are better equipped to manage the ups and downs of life.

Support in Childhood Pays Off in Adulthood

A 2017 “ACEs and Resilience” study conducted by the National Health Service in Wales found that, overall, having supportive friends, opportunities to engage with their community, people to look up to, and other sources of resilience in childhood more than halved the current mental illness in adults with four or more ACEs from 29% to 14%. Adults who acknowledged having childhood protective factors reported a reduced rate of suicidal thoughts and self-harming of 19% versus those without protective factors, who reported 39%.

We know that resilience requires that a child can rely on the presence of at least one supportive, caring adult. But who are these people? Are you one of them? Every child is surrounded by adults who can help them: family members, friends, neighbors, teachers, counselors, coaches, medical professionals, etc. These positive adult role models can be a buffer in a child’s life. A buffer is like a shield that helps to block some of the negative effects of ACEs exposure.

We’ll share more about being a buffer in our next blog.

Sign up for our newsletter to stay up-to-date on our Fighting ACEs initiative.

Sign up now for news, events, and education about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and promoting resilience.

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive emails from: Center for Child Counseling, 8895 N. Military Trail, Palm Beach Gardens, FL, 33410. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email.

The event’s keynote speakers from the

The event’s keynote speakers from the