The Issue of “Other ACEs”

The concept of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) is based on the 10-question survey originally developed for the first large-scale study on the subject conducted by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and insurance giant Keiser Permanente from 1995 to 1997. Using a purist’s definition of ACEs means we only consider the ten questions designed to identify incidents of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction that might cause the kind of sustained toxic stress that define adversity and have lifelong mental and physical health implications.

Specifically, the initial questionnaire sought to unearth experiences that included:

• Physical, emotional, and sexual abuse

• Loss of a parent/caregiver to death, divorce, or incarceration

• Substance abuse and mental illness in the family or home

Keeping to the original ten questions allows for the accurate collection of data, as it ensures we compare ‘apples to apples’ and generate clean results. However, being a trauma-informed and ACEs-aware member of society doesn’t just mean knowing what ACEs are. We need to become a kind of mental detective to understand what else ACEs might be. We must identify situations that could be traumatic and develop insight into what causes feelings of sustained fear and anxiety in a child. It’s a bit like the difference between the letter of the law and the spirit of the law. One is a narrow, clear definition and the other seeks to understand implications beyond the literal (often limiting) definition.

As discussed in an earlier blog, we know that it’s really the repeated activation of the body’s natural flight, flight, or freeze response that causes the damage that might result in issues and challenges down the road. This prolonged toxic stress in the absence of positive buffers is what results in developmental issues, so whatever might cause toxic stress should draw our focus, not a strict list of specific yes or no answers.

By now, we also have a greater understanding of the mirror issue of Adverse Community Environments. Children growing up in communities where socio-economic deprivation is prevalent are likely to suffer higher doses of adversity, so we can expect higher levels of toxic stress among children in areas where poverty, discrimination, violence, substandard housing, and general lack of opportunity, economic mobility, and social resources are common.

Along with generally adverse environments, let’s consider some other negative experiences that weren’t explicitly identified in the original study but which can clearly result in toxic stress in the absence of effective buffers.

Accidents and/or Medical ACEs

Most of us have had an accident or undergone surgery of some kind in our lives. While stressful, these experiences fall into the short- or mid-term, tolerable type of stress because we deal with them, heal in an appropriate time period, and move on with our lives. This is especially true if the procedure is scheduled and we have time to plan for it; stress increases in correlation to the speed of the onset of the incident/condition, the complexity of the issue, and long-term, unexpected consequences of the event itself. The same is true when a child experiences the absence of a parent/caregiver due to an accident, or when a child experiences an accident or unexpected hospitalization.

The original ACEs study identified incarceration of a parent/caregiver as a potential ACE. The creators of the study obviously envisioned the long-term implications of the loss of a primary source of attachment from a young child’s life, but it’s not just death, divorce, or incarceration that can remove a caregiver. A severe accident that suddenly results in the loss of a parent can be difficult for a young child to understand. It can result in a change of caregiver or even a complete change in the home environment, leading to uncertainty, insecurity, failure to securely attached to an adult figure, and the toxic stress associated with those events. The same can also be true when a child endures an accident themselves, or suffers a severe illness that removes them from their home, especially when it involves insecurity and long periods in a hospital or rehab facility.

Of course, millions of children experience these events and come through them unscathed thanks to devoted parents, skilled counselors, and caring medical staff. Again, it is not necessarily the experience itself but rather the absence of a positive buffer in the face of the experience that really counts. This is why it’s so important to ensure that experiences are adequately explained and properly processed by children. It can make all the difference between an experience that results in healthy memories of personal resilience or one that causes lifelong psychological scars.

Institutionalized Abuse ACEs

The countless sexual abuse scandals that have rocked the world over the past few decades illustrate another type of ACE that has plagued our children. While sexual abuse is included in the original study, the institutional nature of church- or faith-based sexual abuse adds a whole new layer of complexity to this traumatic experience. Often, the abuser is associated with goodness and virtue; in some cases, the abuser is a direct appointee or representative of God himself in the child’s mind. Intertwining issues of religion, deep trust, and faith with the abuse scenario is psychologically devastating.

The millions of suffering victims worldwide show how insidious this kind of abuse can be. Survivors may require highly-skilled therapists to help them work through the issue while still maintaining their faith (should they wish to do so).

Child sex trafficking is an established system of abuse (albeit a black market one) that occurs in every country. In some regions of the world, a very real child sex tourism industry thrives. This degrading and catastrophic abuse results in extreme and complex ACEs among the victimized children as well as the adult victims who have endured these practices in their past.

Culture-Related ACEs

Certain cultural norms are accepted in parts of the world but abhorrent in others. These ‘hot potato’ issues pit individual/religious/personal rights against the accepted morality of the dominant culture and are deeply sensitive. One example of a cultural ACE is Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) which is a silent scourge that affects 200 million girls and women in approximately 30 countries in Africa, Asia and the Middle East. It is a growing issue in western society due to increasing immigration. FGM includes all procedures involving partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons. The mutilation is performed, usually by unskilled practitioners with little to no medical training, on girls from infancy to +-16 years old and is a violation of basic human rights — undoubtedly an ACE. The “ceremony” itself is traumatic, often conducted without anesthetic, and the lifelong consequences associated with it can be devastating. The numerous physical issues of infection, difficulty urinating of passing menstrual flow, infertility, pregnancy and childbirth complications can start in childhood and last for a lifetime. The guilt, shame, sense of otherness, and silent stigma of FGM can mean decades of suffering for victims of the practice.

Child marriage s another traumatic experience that is most common in certain Eastern culture but also still entertained by some cults and splinter groups in the United States. These circumstances may seem rare but without a doubt they do occur and would certainly qualify as adverse experiences for children.

ACEs Caused by War or Unrest

Societies in turmoil expose children to extraordinarily damaging experiences. Innocent victims of war, unrest, riots, or corrupt or inhumane political systems (such as the historic period of apartheid in South Africa or the current oppression of North Korea) undoubtedly carry the wounds and scars of their childhoods with them into adulthood. Many have witnessed brutal crimes like murder and rape, the results of terrorism such as explosions and genocide, as well as torture and the decimation of their communities. Again, this may seem extreme, but remember that millions of children worldwide are exposed to these events. Increased global mobility and the rise in numbers of people seeking refugee status in haven countries for these very reasons, it is not unreasonable to think we may encounter children suffering the effects of these devastating issues.

Racism Causes ACEs

Some types of ACEs are very prevalent closer to home. Studies show that racism is a deeply affecting adverse experience. Children from many minority groups (based on race, religion, disability, or national origin) suffer high doses of toxic stress resulting from the prejudice and hatefulness of others. You can learn more about how minorities experience ACEs to a disproportionate degree in our previous blog on ACEs and Minorities.

Technology-Associated ACES

Technology is evolving at a rapid pace, often faster than we can come up with ways to protect our children from exposure to unhealthy experiences. There has been a movement to include bullying (especially cyber bullying) as an ACE, as it can be protracted, isolating, and extremely emotionally damaging. In the worst cases, elements of blackmail may be involved where bullies hold the threat of sharing inappropriate or damning images or videos over the heads of their victims. The suicide rate among young and very young children is often correlated to bullying. There have been cases of suicide by children as young as 8 or 9 due to their inability to cope with the intense anxiety and fear of being in such a situation without perceived adult support.

The onus is on parents, teachers, and caregivers to:

1) Be vigilant in monitoring their child’s screen time and online interactions

2) Make sure their child knows they are always available to talk things through no matter what the situation might be

3) In general, it is appropriate to complete a contract with younger children that clearly includes an agreement of how/when the cellphone will be used, that the adult will always have free access to any of the child’s online activity, and that there are consequences for breaking the rules. Kidsafe Foundation has some great tools on their website, including internet safety tips and ideas for phone contracts.

Another aspect of increased screen time is the possibility of exposure to damaging age-inappropriate and material. This could include things like films with mature content, violent video games, and pornography. Depending on the nature and intensity of the material, repeated exposure can be considered an adverse experience particularly if a child sees very dark materials on a regular basis. Bear in mind that predators use pornography to groom and desensitize young children and make them vulnerable to abuse. While adults have the developmental ability to process and assess extreme material, young children do not. Early exposure to adult material can have a host of potential mental and physical health implications later in life including guilt, anxiety, inappropriate sexualization in very young children, promiscuity or sexual acting out, eating disorders, substance abuse, and many others.

Unearthing All ACEs

These examples of other ACEs are by no means a definitive list. Hopefully, they offer a starting point for a new way of thinking about ACEs because childhood trauma is not limited to the ten experiences identified in the original ACEs study. We need to work under the “spirit of the law” to identify what might be traumatic and cause long-term toxic stress in a child, causing developmental delays, brain functioning abnormalities, and difficulties with learning, forming happy relationships, and being a positive member of the community.

As we practice using our trauma-informed radar, more and more examples of potentially damaging experiences might come to us. By understanding what could negatively affect a child in the long term, we can equip ourselves to provide the antidote. We can only be effective buffers against trauma if we fully understand not only what ACEs are but what else they might also be.

Sign up now for news, events, and education about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and promoting resilience.

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive emails from: Center for Child Counseling, 8895 N. Military Trail, Palm Beach Gardens, FL, 33410. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email.

Teachers as Buffers Against ACEs

We give teachers unprecedented access to our children. We entrust them to educate our children but we also allow them to influence our children’s thoughts, attitudes, and behavior for many hours every day. Fortunately, most teachers are special, dedicated people who care deeply for the well-being of little ones. Teachers also have a profound opportunity to positively affect the life of a child with ACEs. For this reason, teachers can be powerful buffers against adversity and should have all the knowledge and support they need to meet this enormous challenge.

We all know that teachers are basically superheroes. Many of us have a special teacher in our past, someone who came into our world at a crucial time and possibly changed the course of our lives. Even people who don’t have fond memories of school acknowledge that being a teacher is a calling more than a career, especially since teachers are often considered overworked and underpaid. Teachers tend to give of themselves above and beyond what could reasonably be expected. The very best teachers sacrifice their personal time and money to give their students richer learning experiences. These caring professionals may sometimes feel unappreciated, but they play a crucial role in supporting our children – not only in their academic pursuits, but in their development as flourishing, fulfilled human beings.

School is a Pivot Point in a Child’s Life

A child’s first experiences, positive and negative, come from interactions with their immediate family members or caregivers. After the age of 5 or 6 (and often younger) a new area of influence enters their lives: kindergarten or school. At school, children meet peers and teachers. Adjusting to mixing with other children who are not siblings is a challenge even for a well-adjusted child. For a child who has not benefitted from strong family supports, it may be almost impossible. Their backgrounds have not prepared them for life lessons like:

• Sharing, fairness, and negotiation;

• Self-expression of emotions, creativity, and personality;

• Kindness and compassion; and

• Simply getting along with others.

Sadly, every year millions of children start their school careers with very little preparation from the home front. They may come from chaotic, deprived, or even abusive backgrounds. They are among the 20% of little ones starting school disadvantaged by at least two ACEs. This puts them at risk for mental and physical health issues and diminishes their ability (at a bio-chemical level) to behave appropriately and be academically successful. There’s no doubt that teachers of very young children are up against many challenges!

Teachers likely spend more time with young children than their parents do. They are uniquely positioned to identify:

• Children struggling to adapt to school;

• Children with learning difficulties like dyslexia, ADHD, and numerous other concerns; and

• Children with physical challenges like vision, hearing, or coordination issues.

So, while already tasked with a full load of teaching and testing requirements, teachers are also often responsible for the social-emotional wellness of the little people in their charge.

Why Do Teachers Play This Role?

Of course, teachers don’t necessarily relish this aspect of the job. Their primary assignment is to educate but many are thrust into the position of having deal with emotional and behavioral issues simply to maintain order in their classrooms. It can be a constant battle to ensure that the many children trying to learn are not disrupted by the few who are “acting out”. How teachers approach this juggling act is absolutely crucial.

Throughout this series, we have learned about the alarming prevalence of ACEs. The statistics show that every classroom in America has several children who are trying to cope with experiences that even adults would struggle with. These issues are amplified in neighborhoods experiencing Adverse Community Environments (the mirroring component of the Adverse Childhood Experiences issue). Schools are challenged when they are located in areas troubled by inequity, poor resources, gang violence, weakened social supports, high rates of unemployment, and poor maintenance of communal areas like parks, roads, and sidewalks. These schools, which would benefit the most from prevention and early intervention childhood mental health services, often receive the least attention. Their teachers may be facing the most daunting and complex problems.

Organizations like the Center for Child Counseling can make the most impact in these neighborhoods. Our skilled therapists are co-located in more than 30 schools (as well as numerous community centers) in at-risk zip codes but they alone cannot have as much influence as the numerous teachers working in those areas’ schools.

What is the Most Important Thing in a Classroom?

It’s not the behavior of the children, the number of students, or the facilities available in the school. When it comes to building successful children, the most important aspect of every classroom is the ATTITUDE OF THE TEACHER. Children are sponges who absorb words, feelings, and the atmospheres in which they live. They look to their teachers to provide examples and guidance about how to behave. The way teachers choose to respond to every situation with a child either escalates or deescalates that situation.

A child who smashes a toy in a rage can be labelled in a teacher’s mind as bad or naughty. However, the behavior can also be identified by the teacher as an indication of some intense emotion that child is experiencing. By avoiding the label of “bad”, teachers can decide to see this behavior as an opportunity to intervene and teach a great child who is full of potential! Accepting a child for who they are, even in moments when their behavior is challenging, means teachers can reserve judgement and avoid sending the message to a child that they are disliked, a failure, or simply a bad kid.

Attitude and acceptance work hand in hand to help build self esteem and resilience in children, and we already know that these qualities serve as antidotes to the adverse experiences they may be experiencing at home or in their community.

Special Care for Educators

Of course, all teachers were once children, too! Many teachers still carry the burdens of unresolved childhood adversity with them. They can bring their own pain, sadness, and insecurity into the classroom where children’s behavior can serve as a trigger that churns up past emotions. It’s vital for teachers to identify their own ACEs, what triggers negative feelings in them, and key ways to cope not only with a child’s behavior but their own responses to it.

We Offer Support for Teachers

Our training, designed specifically for teachers, offers practical, useful advice to help teachers become more trauma informed, so they can be the strongest possible buffers for our children. Society has assigned teachers a sacred role and we need to equip them to fulfill their calling to the best of their ability.

Our specialized therapists co-located in elementary and middle schools throughout Palm Beach County provide direct support to both students and teachers — a model that’s truly unique. Our approach offers prevention, early intervention, and targeted services for children while also creating a wraparound supports for teachers that build a positive learning environment throughout the school.

If you’re a teacher, or the parent of a child, ask for our training at your school. We offer basic and advanced modules through our Institute for Clinical Training. As members of the community, let’s support our teachers because they really are the front-line troops, the crucial buffers, against adversity in our war with ACEs.

Sign up now for news, events, and education about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and promoting resilience.

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive emails from: Center for Child Counseling, 8895 N. Military Trail, Palm Beach Gardens, FL, 33410. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email.

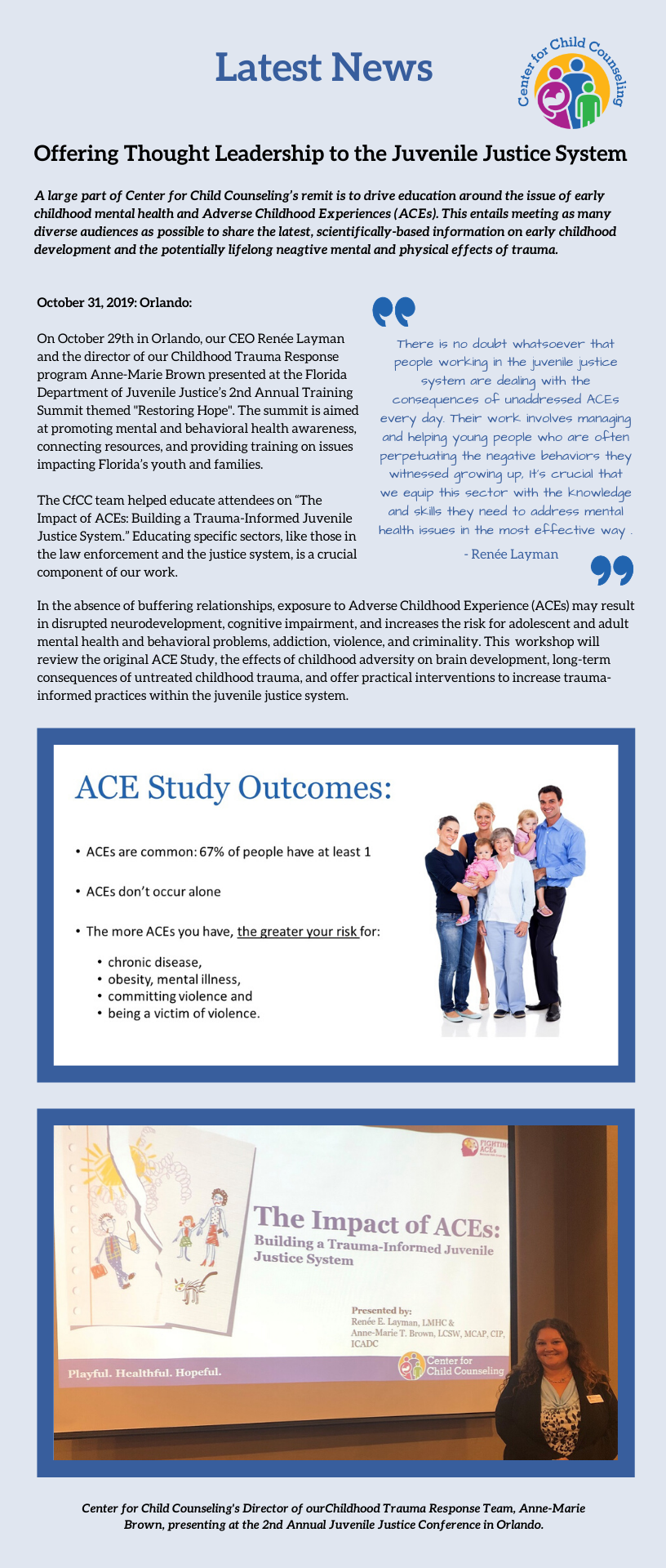

Safari, Ltd. Delivers More Than Just Toys…

A recent donation of boxes full of toys from Safari, Ltd. will make a big difference in the lives of children receiving Play Therapy at Center for Child Counseling to help them heal from trauma and abuse.

July 1, 2019 — Play Therapy is one of the most effective ways of working with children who have experienced abuse or trauma. Highly-skilled, specially-trained childhood mental health therapists, like those at the Center for Child Counseling in West Palm Beach, Florida, use toys to communicate and interact with children as young as two years old. “Play is a child’s language age and toys are their words,” explains the Center’s CEO, Renée Layman. “We use established best-practice techniques and we operate Play Therapy rooms at our Child and Family Center and in numerous community-based locations.”

Safari, Ltd. has made a tremendous difference in the lives of children visiting the Play Therapy rooms by donating a truckload of their toys to the Center. Since 1982, Safari has created hand-painted learning toys for kids — from dinosaurs, to wild animals, to mythical creatures. Their detailed models help children understand the world they live in. They fuel the imagination, promote creativity, and give hours and hours of playtime fun. Most importantly, they’re built to last!

“This donation means the world to us,” says Stephanie de la Cruz, Center for Child Counseling’s Director of Clinical Services. “Our clients use sandboxes to build scenes and tell stories; they use the toys to express their fears and show us situations and experiences. Toys are crucial elements in our work. The quality of Safari’s toys makes them both beautiful and durable.”

Many of the Center’s clients need financial assistance with their services. “Not having to outlay money for toys means we can use that money to support direct services for the children we help. That means more children will get the therapy they need to begin to heal,” says de la Cruz. “We’re so grateful to Safari for giving back in this way. Their gift will bring so much joy to children who, we believe, always deserve to be playful, hopeful and healthy.”

Abigail Beebe, Chair of Florida Bar Family Law Section, Chooses Center for Child Counseling for $5,000 Award

The 2018-2019 Chair of The Florida Bar Family Law Section, Abigail Beebe, has selected Center for Child Counseling as the recipient of a $5,000 annual honorarium which is awarded each year to a deserving local nonprofit selected by the outgoing chair for their work on behalf of children interacting with the judicial system.

June 28, 2019: West Palm Beach: The area of family law in Florida’s courts present some of the most challenging and emotional cases in the legal system. Situations involving children and families can be sensitive at best and fraught with tension and anger at worst. That’s why the outgoing Chair of the Florida Bar Association’s Family Law Section, Abigail Beebe, awarded a $5,000 honorarium to a local childhood mental health nonprofit, Center for Child Counseling, which works to help children and families experiencing trauma and abuse begin to heal. “I wanted to select an organization that was getting to the root of what causes so many of our families’ issues in the first place,” explains Beebe. “Center for Child Counseling addresses adversity in individual homes and families interacting with the court system as well as social inequity in the community at large. They bring a special kind of compassion and commitment to their work and really advocate for the best interests of our children.” The honorarium is allocated to the outgoing Chair each year to be awarded at their discretion.

Lauren Scirrotto, LMHC, Chief Program Officer and Eddie Stephens, Board Member (and Family Law Section Member) accepted the check on behalf of Center for Child Counseling. “I work with the Center because I know the effects Adverse Childhood Experiences had on my life as I was growing up,” says Stephens who is an equity partner at Ward Damon. “It’s so important to provide children with positive adult role models that can help buffer the effects of this kind of adversity and keep children on a healthy path in life.”

Sound Solutions for Children’s Mental Health

A generous donation of noise-mitigating wall art from Audimute is going to make all the difference to Center for Child Counseling’s new Child and Family Center offices and play therapy rooms located in the Palm Health Pavilion at St. Mary’s Medical Center.

Children at play are noisy — just ask any parent! Now imagine you work with exuberant children all day long and that your offices share walls and hallways with their playrooms. The din can be pretty disruptive. That was the situation for dozens of therapists at the Center for Child Counseling in our wonderful new offices located in the Palm Health Pavilion on the grounds of St. Mary’s Hospital in West Palm Beach. CfCC’s Child and Family Center moved into the new facilities in January and have been getting settled in but finding a happy sound balance between our playrooms, which can be loud and our offices where we need to do careful reporting and administrative work was a challenge.

Now, we’ve had help solving that problem thanks to an incredibly generous donation from Audimute, a company that specializes in producing eco-friendly, sound-dampening acoustic solutions for residential, commercial, and industrial applications. Audimute donated hundreds of acoustic tiles–8 boxes full, in fact–to us for their walls. Audimute has its headquarters in Cleveland, Ohio, far from our home base. But that was no problem for Audimute…they picked up the shipping costs to deliver the products, too!

When our therapists opened the boxes, they were amazed at the variety and quality of the tiles – all designed to delight children. “Play is a child’s language and toys are their words,” explains CfCC’s CEO, Renée Layman. “That’s why we use play therapy with our clients who can be as young as two years old. Many of these children are suffering the effects of abuse and trauma. Having a bright, cheerful, safe place where they can just have fun and express themselves alongside a skilled therapist goes a long way to help them on their journey to recovery.”

The hundreds of donated tiles instantly brought new life to the organization’s play therapy rooms. “They’re terrific as art and to ensure privacy for our clients,” says Stephanie de la Cruz, the Center’s Director of Clinical Services. “They’ve also transformed our offices into tranquil places we can enjoy.”

Center for Child Counseling wishes to thank Audimute and its Founder and President, Mitch Zlotnik, for their caring and creative commitment to our kids. Your contribution helps make therapy a less daunting experience for children who we believe should always be joyful, playful, and hopeful.

Community Leaders Unite Against Childhood Trauma

Center for Child Counseling (CfCC), Palm Beach County’s preeminent agency in the field of childhood mental health, brought together leaders from the public and private sectors to jumpstart an action plan to address childhood adversity.

Last week’s 3rd annual “Lead the Fight: ACEs to Action” event represented a milestone in addressing the basic human right of all children in Palm Beach County to lead lives free from trauma and adversity. The County’s leaders in mental health, business, education, law enforcement, healthcare, and the judiciary assembled to tackle the most pressing public health issue facing our communities today: Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), which carry lifelong physical and mental health implications and result in exorbitant costs to taxpayers, financially and in terms of social ills. The event was attended by 289 VIPs from across Palm Beach County and beyond.

Based in Palm Beach County, CfCC offers mental health services to children from birth to 18. The nonprofit agency specializes in helping to heal young children exposed to trauma and has emerged as the local leader in the fight against ACEs. They also work to educate the public about the prevalence and profound negative effects of childhood trauma by conducting an awareness campaign focused on training teachers, healthcare providers, and community leaders to view their interactions with people, especially children, through a more trauma-informed lens. This year’s “Lead the Fight” event was aimed at uniting important stakeholders to tackle ACEs by putting research-based plans into action.

CfCC’s CEO, Renée Layman, describes her commitment: “It’s the most crucial work we can do. We raise the future in our children…how we choose to harm or help them determines the kind of future we can bank on. We know that prevention and early intervention is the key to ensuring healthy childhood development, but we keep failing our children even though most societal issues, including soaring rates of teen depression and suicide, school shootings, substance abuse, incarceration, and domestic and community violence, all have their roots in childhood trauma that was never adequately addressed.” In recent years, research has proved that adverse experiences and trauma effect the physiological development of a young child’s brain and cause a lifetime of issues. “We need to prioritize efforts that get help to children when they first need it; we need to fund these efforts.”

The event’s keynote speaker was Dr. Neil Boris, Medical Director of Circle of Security International and President of the Florida Association for Infant Mental Health, who shared the social consequences of missing the opportunity to intervene and help children as early as possible.

Amber Payne, CfCC’s Director of Community Engagement and Development, presented the findings of a White Paper entitled: “A Public Health Approach to Fighting ACEs in Palm Beach County: Opportunities for Levers of Change and Innovation”. The paper which assesses the County’s readiness to respond to this public health crisis, was underwritten by local health funder Quantum Foundation and provides best-practice solutions to help different sectors identify ways to work with children who are facing adversity.

As Ms. Payne explains: “We know that people with high levels of childhood adversity suffer throughout their lives and die, on average, 20 years younger than those without these experiences. There is hope, however, because research shows that introducing just one positive adult influence in a child’s life can make all the difference to the trajectory of that child’s future path. We want to equip people to promote and provide those buffering relationships to our children.”

CfCC offers training opportunities for those who wish to learn more. As Renée Layman explains. “We want people to know their ACE score and understand the implications of that score. Knowledge is power,” she said. “If you can understand how ACEs have affected you and how they might be affecting your children, you’ll be able to break the intergenerational cycle of abuse and start on the road to healing.”

Learn more about CfCC's Fighting ACEs work or to take the free, anonymous 10-question ACE survey right now.

The Power of Language: ACEs and Trauma

ACEs and trauma are different. Gain an accurate understanding of adversity, ACEs, trauma, and toxic stress to fully understand how best to fight adverse experiences in childhood.

Language, or the words we choose to describe experiences to ourselves and others, is powerful. Words influence the way we think, and how we choose to think about ACEs and trauma influences our actions. So often, we use the term ACEs and the word trauma interchangeably, but they are different. While this educational series is part of our Fighting ACEs campaign and therefore focused on ACEs, we cannot afford to ignore the full range of childhood adversity, including social inequity, and how children can respond to it in many ways.

Before we get into definitions, it’s important to remember some concepts we’ve discussed before. Every child is unique from the genetic level up. The way they react to trauma can and will vary dramatically. Because their brains are still growing, children are vulnerable to situations that can alter their chemistry and hamper normal brain development. But they also have neural plasticity which makes them adaptable and responsive to healing interventions. Two children (even siblings living in the same home…even twins!) might experience the same traumatic event then process and respond to it very differently. There are no rules for how we can expect a child to react or behave after a traumatic event. Of course, expert therapists trained in childhood mental health, like those at the Center for Child Counseling, can make some predictions based on years of experience and work with a child accordingly.

Certain types of childhood adversity are especially likely to cause trauma reactions in children, such as the sudden loss of a family member or witnessing intense domestic violence. Other events, like divorce or separation result in a wider, less predictable range of responses. Some children are deeply traumatized when their parents divorce; some fare well and may even thrive, especially if the divorce removes a negative influence (such as an abusive, alcoholic father) from the picture thus stabilizing the relationship between mother and child.

General Adversity in Childhood

Let’s consider adversity in general. Adversity describes any number of situations or events that threaten healthy development for a child, both physical and psychological. Adversity can include circumstances like abuse, neglect, domestic and community violence, bullying, extreme poverty, and discrimination. Adversity tends to be a condition that exists for an extended period of time; it is not a one-time event. Adversity is a general living condition that is often, or always, present.

Certain groups of children, including minorities, receive a disproportionate dose of adversity because they belong to a group that has been historically disadvantaged and continues to face the challenge of inequity. Science shows that enduring adversity for long periods can affect the developing brains of children, resulting in lifelong physical and mental health issues. However, adversity is only one half of the equation because it seems that even the most harmful experiences can be balanced out, or even negated, if a strong support system is in place.

ACEs Defined

General adversity is not the same thing as ACEs which are a clearly identified set of adverse situations. ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences) is an acronym that emerged after a study originally conducted by Kesier Permanaente and the Centers for Disease Control in the 1990s. This study was the first to identify a strong correlation between certain adverse experiences in childhood and poor physical and mental health outcomes (e.g.: heart disease, diabetes, substance abuse, depression, etc.) later in life. The term ACEs describes a more specific set of adverse experiences outlined by the original study and subsequently added to.

The original study placed adverse experiences into seven specific categories based on 10 questions:

- physical, sexual, and emotional abuse

- a mother who was treated violently

- living with someone who was mentally ill in the household

- someone who abused alcohol or drugs in the household

- incarceration of a member of the household

ACEs vs. Trauma

So how do ACEs differ from trauma? Trauma is one possible outcome of prolonged exposure to adversity. We tend to think of a trauma as a sudden, cataclysmic event like a serious car accident or a tornado. While it’s true that those experiences can qualify as ACEs, trauma is also the result of sustained periods of toxic stress over weeks, months, or even years.

The original ACE questionnaire was not definitive. More recent, expanded studies have added questions about peer victimization (bullying, etc.), serious physical illness in the household, especially where the child might become a caregiver, and one-off traumatic events with long-term consequences (a car accident, for example). No survey can cover the full scope of what might be an adverse experience for a child, not only because the variables are endless but also because not every child sees or responds to the same experience as an adverse one. Adversity and ACEs are, to some extent, in the eye of the beholder. What is traumatic is very much about perception. This perception is often unconscious or automatic rather than a considered reaction.

In simple terms, not every child who experiences a traumatic event is traumatized by it.

When a child experiences an adverse situation, let’s use a school shooting as a sad example, in the moment they will feel the associated emotions (terror, panic, helplessness) and the physiological responses (rapid heartbeat, adrenaline surge) as well as the after-effects which may manifest themselves immediately or much later. These manifestations may last far beyond the event itself and can include responses like bedwetting, nightmares, and stomach aches.

The same is true of the intensity of the experience. A child who witnessed the shooting and saw friends harmed or killed versus a child who was in the school during the event and experienced the panic but did not necessarily witness anything, might behave differently. The services they will need will likely differ, too, but again this depends on genetic vulnerabilities, prior experiences that have damaged the stress response system, or the presence of limited healthy gene expression (learn more about gene expression in our post about epigenetics).

PTSD and Toxic Stress

While the event is the same, two aspects may be very different: the physical experiences of the event and the individual’s response to it which can be based on nature (genetic resilience), nurture (coping skills that have been learned) and the support they have received in their lives thus far as well as the support they receive after the event i.e.: the immediate presence of crisis-trained buffers as well as the support of long-term buffers. Of course, one child who experienced the shooting may recover quickly without significant distress, whereas another may develop Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and benefit from professional help and services – crucially, those provided by a trauma-informed team of caregivers. Swift intervention can certainly help children express and deal with the aftermath of an intense traumatic event, mitigating or buffering against that stress and preventing it from harming their development or well-being.

If trauma is unaddressed and prolonged, it can result in toxic stress which we’ve discussed at length in an earlier post in this series. It is really the effects of toxic stress on the body that can result in lifelong negative outcomes. Toxic stress wears down the body’s natural response systems over time and is the real villain in the story of ACEs, building up insidiously and causing countless potential future ills for the individual and for society.

Knowing Better = Doing Better

As our understanding of adversity, trauma, and ACEs grows, and as awareness grows among sectors who work with children and the general public grows, too, opportunities to intervene will reveal themselves. Some opportunities are already self-evident, however. Knowing that adverse community environments breed ACEs, we can focus on children living in these conditions who are most likely to need therapeutic intervention. We can provide preventative and early intervention services to support these children and avoid retraumatizing them. Sound knowledge can also help us avoid over-diagnosing or over-medicating children who are responding well to their circumstances or demonstrating the resilience that is the antidote to toxic stress

Let’s be specific in our language and avoid jargon and catchphrases which don’t accurately describe the situation. Labels can be vague and dangerous. The more specific we can be with our words and their meanings, while understanding the differences and uniqueness of each individual, the more effective we will be as buffers and healers for our children.

Sign up now for news, events, and education about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and promoting resilience.

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive emails from: Center for Child Counseling, 8895 N. Military Trail, Palm Beach Gardens, FL, 33410. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email.

Double Win for Childhood Mental Health in Palm Beach County!

Center for Child Counseling is ‘two for two’ with local Impact organizations

Center for Child Counseling has been awarded not one, but two grants totaling $200,000 from both the north county and south county women’s giving organizations, Impact the Palm Beaches and Impact 100. The funds will be used to transform the lives of children experiencing adversity and trauma by providing four elementary schools with innovative, research-based prevention and early intervention mental health services and education.

In a first since their inceptions, the southern-based and northern-based chapters of the Impact charitable organizations have both selected us as their 2019 grantees, which means we’ve been recognized as an outstanding nonprofit from one end of the County to the other!

The first award was made by Impact the Palm Beaches, based in West Palm Beach, at an event held on Thursday, January 31st at the FITTEAM Ballpark of the Palm Beaches. This event represented the final stage in a year-long search to identify and support worthy local projects that are innovative and transformational. Center for Child Counseling received top honors, walking away with the $100,000 grant.

The second win came on Wednesday, April 17th when Impact 100, based in Boca Raton, awarded Center for Child Counseling $100,000 at an evening event held at the Lynn University campus.

These grants will be used to support Center for Child Counseling’s school-based mental health programs which offer prevention, early intervention, and direct services. Since the aim of the grants is to transform schools one at a time, the awards will be used to pay for specialized child therapists to provide mental health education and support at four elementary schools which are eager to welcome the program.

The therapists will work with children, families, and their caregivers – helping them manage behaviors, cope with challenges, and regulate emotions that can lead to mental health concerns later in life. This unique model brings a calmer, more positive atmosphere to the whole school and promotes an environment of security that is conducive to learning.

The therapists will also educate and train school staff, teachers, and parents about the impact of ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences) and how they can have a lifelong effect on a child’s mental and physical health.

“It’s our goal as local leaders in this field to ensure we have a trauma-informed community,” said CfCC’s CEO Renée Layman. “The women of Impact the Palm Beaches and Impact 100 clearly recognize this need and have supported our research-based model for schools with their wonderful grants. We thank them, and our community’s children thank them.”

Implementation of the project at the four schools is planned to begin immediately.

More about the Center for Child Counseling:

More about the Center for Child Counseling:

Center for Child Counseling is building the foundation for playful, healthful, and hopeful living for children and families in Palm Beach County. We work to ensure an ACEs-aware and trauma-informed community with a focus on preventing and healing the effects that ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences) and toxic stress have on developing children by promoting coping skills, resilience, and healthy family relationships. To learn more about the Center for Child Counseling or its work, visit centerforchildcounseling.org

More about Impact the Palm Beaches:

More about Impact the Palm Beaches:

Founded in 2015, Impact the Palm Beaches is a unique organization of dynamic women who make transformational change in their local community through collective philanthropy. Impact members each contribute $1,000 annually and award a $100,000 Impact grant. Impact the Palm Beaches serves the northern portion of the county from Lake Worth to Jupiter. To learn more about Impact the Palm Beaches or its work, visit impactthepalmbeaches.org

More about Impact 100:

More about Impact 100:

Impact 100 Palm Beach County is a women’s charitable organization funding local nonprofit initiatives. It is comprised of a growing number of women (532 members last year) who donate $1,000 annually, pool their funds and vote to award multiple $100,000 grants to local nonprofits in southern Palm Beach County. The organization is a progressive leader in women’s philanthropy, committed to strengthening our community through the collective resources of our members by awarding high-impact grants in five focus areas: Arts & Culture, Education, Environment, Family, and Health & Wellness. To learn more about Impact 100, visit impact100pbc.com

Epigenetics and ACEs

Reading the word “genetics” in the title of an article fills most of us with dread. We won’t understand it. We don’t even remember the basics from school. Genetics is such a complex field of study that it won’t make sense to us. But please read on because the possibility of a connection between genetics–or, more accurately, epigenetics–and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) could uncover startling revelations about how we should be raising our children.

Let’s start at the beginning. Genetics is a branch of biology concerned with the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity—or the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring—in living organisms.

For many people, knowledge on the subject is limited to a few simple facts:

1.) We all have genes that we got from our parents.

2.) Genes carry our inherited information or genetic code.

3.) Genes are responsible for characteristics like eye color, height, hair color, etc.

4.) Genes also account for less tangible traits like whether we will be susceptible to certain diseases, or even if we will be optimistic and resilient, or prone to

alcoholism or depression.

Some of us may remember a little more of what we learned in high school science class, but here are the basics:

• Human cells can house about 25,000 – 35,000 genes, which are carried on structures called chromosomes.

• As a human being, you have 23 pairs of chromosomes (46 total) – half from your mother and half from your father. Your genetic makeup is determined

when your father’s sperm fertilizes your mother’s egg at conception to produce the materials needed to make a new, unique individual – you!

• Each gene on the chromosomes has a function. The DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) in a gene spells out specific instructions—like a cooking recipe — for

making proteins in the cell.

• Proteins are the building blocks for everything in the body from bones to muscles to blood. Proteins help our bodies grow, work properly, and stay

healthy.

Genetic processes don’t occur in a vacuum, however. They can be greatly influenced by our environment and experiences which, in turn, can affect our development, decision-making, social-emotional wellness, and behavior. But how much of who we are is due to our genetic code and how much is the result of how and where we were raised and by whom? This is often referred to as the nature versus nurture argument.

Identical Twins and Nature vs. Nurture

Consider the example of genetically identical twins separated at birth and raised in different homes. One child ends up in a chaotic, insecure environment where he suffers ACEs and trauma. The other child grows up surrounded by love and kindness; he is provided with close personal bonds, diverse opportunities, and encouragement. While the nature of the identical twins might be genetically determined to be equal, the nurture component is clearly different. The child raised in the austere, uncertain climate may develop at a slower rate and have greater difficulties in school and life than the nurtured twin. The toxic stress associated with his ACEs has delayed his cognitive and behavioral development, disadvantaging him from birth.

How much of who we turn out to be is the result of genes and how much is the result of our environment is an age-old debate that has not yet been settled. Most scientists accept that both nature and nurture are at play in all human development. There is, however, a growing body of research that suggests a great deal of who we are is up to our genes. Genetics is an incredibly complex (and often misunderstood) field of science and breakthroughs are made every day. Decoding who we are and what kind of lives we will lead is a great mystery, one of the last great frontiers of human exploration and discovery.

The Concept of Epigenetics

Let’s take the concept one step further into the realm of epigenetics. Epigenetics is the study of cellular and physiological phenotypic trait variations that are caused by external or environmental factors that switch genes on and off and affect how cells read genes instead of being caused by changes in the DNA sequence. Huh? That may sound like gobbledygook to most of us, but it simply means that while the field of genetics looks at the expression of the genetic code, epigenetics studies factors that influence the expression of the gene.

Research in the area of epigenetics has concluded that during early life, the environment we live in can affect the way our genes are expressed.

So, environmental factors like security, bonding, and love can alter how our genes switch on and off, or simply operate. Differing genetic expressions can occur without causing any changes (or mutations) to the underlying genes themselves. In essence, the environment we experience, especially when we are young, can affect which of our genes are active (or expressed), and which remain dormant (or unexpressed).

The Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma

This is why we are discussing epigenetics in connection with ACEs. Because, increasingly, research seems to bear out the fact that the toxic stress of ACEs might not only be experienced by an individual but could also be transmitted from one generation to the next at a genetic level. In very simplified terms, it may be possible to pass on trauma to our children and grandchildren, making the implications of ACEs more devastating and far-reaching than we ever imagined.

Some researchers who have studied historic periods of trauma like the American Civil War or the Holocaust now suspect that abuse, neglect, deprivation, and trauma can impair the functioning at some level of future generations who may not even be living in the same adverse circumstances.

Experiments with Mice and Scent

Controlled experiments in mice have allowed researchers to begin to understand the epigenetics of ACEs. A 2013 study found that there was an intergenerational effect of trauma associated with scent. Researchers blew acetophenone – which smells like cherry blossoms – through the cages of adult male mice, zapping their foot with an electric current at the same time. The mice learned to associate the smell of cherry blossom with pain. Shortly afterwards, these males bred with female mice. When their pups smelled the scent of cherry blossom, they became jumpier and more nervous than pups whose fathers hadn’t been conditioned to fear it. To rule out that the pups were somehow learning about the smell from their parents, they were raised by unrelated mice who had never smelt cherry blossom.

The grand-pups of the traumatized males also showed heightened sensitivity to the scent. Neither of the generations showed a greater sensitivity to smells other than cherry blossom, which indicates that the inheritance was specific to that scent.

The science is far from definitive however. Many studies are currently underway and several alternate theories of if and how this is possible are still being debated within scientific circles. One thing is certain: Epigenetics is going to reveal many secrets in the coming years.

Consequences and Hope

The good news is that intergenerational transmission of trauma seems to happen infrequently. The story of human history is rife with trauma. If the transmission of that trauma was inevitable, all of us would be riddled with crippling health issues and developmental delays, and yet most of us are not. Protective factors that seem to mitigate or even prevent transmission in many people are clearly at play. Again, how and why this happens is not fully understood.

Still, the idea that we may be passing on the effects of trauma is a weighty one.

If this is the case, it should change the way we live our lives. Our parents’ and grandparents’ experiences should suddenly take on new relevance to us. Knowing that the consequences of our own actions and experiences could have long-term implications for the lives of our unborn (and yet to be conceived) children should dramatically alter the choices we make. It might even influence how seriously we, as a society, take violence, abuse, trauma, and mental health.

All these possibilities make it more important than ever before that we value and nurture ourselves and protect our mental and emotional wellbeing. ACEs and trauma are not a predetermined route to a disastrous life, they are simply warning markers along the way that encourage us to be self-aware, surround our children and ourselves with buffers, and practice resilience skills and self-care.

“There’s a malleability to the system,” says Brian Dias, researcher at Emory University and the United States’ Yerkes National Primate Research Center, and author of the 2013 controlled epigenetics study in mice. “The die is not cast. For the most part, we are not messed up as a human race, even though trauma abounds in our environment. [I believe that], in at least some cases, healing the effects of trauma in our lifetimes can put a stop to it echoing further down the generations.”

Our goal should be healing the effects of childhood trauma now, so that even the possibility of passing it on to future generations is minimized. As a community, let’s all focus on trying to achieve that.

Sign up now for news, events, and education about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and promoting resilience.

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive emails from: Center for Child Counseling, 8895 N. Military Trail, Palm Beach Gardens, FL, 33410. You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email.